Ecuador Travelogue (part 5)

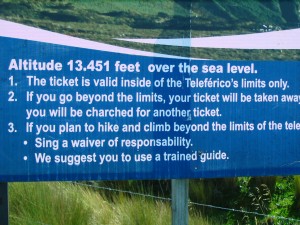

The Teleferico park was surrounded by a fence, and at one point, we came upon a sign warning us not to leave the park and that if we did so, we were on our own and there was nothing they could do to help us. In the relatively short distance, the cloud-covered peak of Ruco Pichincha was visible, and there was a trail that ran along the ridge tops toward Ruco Pichinicha. But as anyone who’s hiked in the mountains knows, what looks to be really close is actually about three hours away. Eileen and I walked toward Ruco Pichincha, but we were never planning on going all the way there, especially since it looked like it was going to rain at any moment.

Later that afternoon, we tracked down one of the policemen from my first English class, Cesar. He had worked up at the Teleferico park for four months and told us a couple of horror stories. Ruco Pichincha, he explained, has some pretty weird microclimate stuff going on, and when it’s surrounded by dark clouds, there’s often an electrical buildup. You’ve got to take anything metal out of your pockets and get out of there, he explained. Once, a family was hiking up on Ruco and they all got struck by lightning. The man’s legs were severed, and the woman was thrown off the peak. They had a boy with them who was also killed.

Cesar went on to explain that a couple of years ago, there was something even worse than lightning lurking in the heights of Pichincha: a rapist. He had a set of binoculars, apparently, and he’d watch for gringo tourists who were vulnerable. We heard some mixed reports from various people, but I think he killed at least one German woman. Cesar was part of an expedition that hiked toward Ruco Pichincha, trying to track the guy down. They didn’t get him that time, but eventually, they captured him, and since he had no teeth, he became known as “El Desdentado de Pichincha,” the Toothless Man of Pichincha. Que horror!

Cesar also told us about another former student of mine — a policeman — whom I’ll call Javi. Javi witnessed a robbery in progress and yelled at the thief, who took off running. Javi gave chase, and caught the guy, but he resisted. The two fell to the ground, and the thief pulled out a huge knife. Javi responded by pulling out his gun. He meant to shoot into the air but instead, he accidentally shot the guy and killed him. It was a clear case of self-defense, but that didn’t make it any easier for Javi to deal with. He got pretty depressed afterwards, and Cesar relayed how horrible Javi felt about it.

The police were in my first English class when I taught in Quito, and though police in general have a reputation of being womanizers and all-around jerks, many of my students were quiet, timid, gentle people. Cesar, “Javi,” and another one they called “El Gordo” (which means fat, but he wasn’t), were among my favorites. Really great guys.

For Cesar, and several others, joining the police force was not exactly a dream come true. Before going to the academy, Cesar was a tennis coach. He began with six students his first year, and by the end of the season, he had 50. He loved it, and he was good at it. But his mom pressured him into joining the police so he could make more money. And now here he is ten years later, still dreaming of returning to coaching.

We spoke to Cesar for a couple of hours that afternoon. I’d gone to the Turism Police headquarters three times, hoping to find some old students, but each time they told me to come back tomorrow or later that afternoon. For whatever reason, I kept missing them. But on my last visit to the headquarters, I asked specifically about Cesar, who, they told me, would be at the Ministry of Tourism all day.

We found the Ministry, and thus Cesar, without too much trouble, and then we hung out with him there until it got dark. That’s the night we went to Zazu, which left us with two more days in Quito.