Wisconsin Film Festival 2009

If there were ever a big street brawl between artists and critics, I’d much prefer to be on the side of the artists. But critics are mean, you say; they live to kick artists’ asses. True. But artists — good ones — know how to use pain. And when the going got tough in this street brawl, the artists would fashion new weapons out of the debris, and the critics’ trash-talking would melt into whining.

Don’t get me wrong. Critics are certainly important; their presence can spur artists to create better work. But the vastly oversimplified explanation that I might someday tell my children goes like this: artists do what they love and critics point out what’s wrong. Now, kids, do you want to be artists or critics?

That said, I’m going to engage in a little bit of criticism, which you should take with a grain of salt. This past weekend, I got to see several movies at the Wisconsin Film Festival. Here are my quick impressions (I don’t spoil plot unless the movie sucks).

My first movie was 500 Days of Summer, directed by Madison native Marc Webb. It was a romantic comedy, actually. But in contrast to most romantic comedies, it was good. It didn’t get its laughs from slapstick humor and references to pot. Instead, it interjected clever nods to other film genres, including, for instance, a choreographed dance number in the street the day after the protagonist, Tom, sleeps with his love interest, Summer. The plot swivels around the fulcrum of Day two hundred and something in the relationship of Tom and Summer. On that particular day, they broke up. So the film has us jumping back and forth between the happier, more hopeful parts of the relationship and the ugly aftermath, which sees Tom having a hard time accepting that it’s over. The non-linearity is great but a little jarring since it’s sometimes confusing when we are in the story. All in all, though, the movie succeeds because it’s a pretty honest portrayal of longed-for relationships and the ways in which we glorify them in our memories.

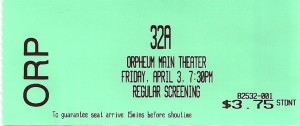

32A is an Irish film about a 14 year old Maeve, who is navigating her entrance into adolescence. At heart, it’s another story about failed relationships. Maeve, a pretty, innnocent, and unassuming girl, somehow gets the attention of 16 year old heartthrob Brian Powers. It’s a relationship doomed to fail, given the huge age difference between them, and most of the film’s tension comes from that inevitability. Maeve gets in arguments with her girlfriends, skips out of school once, smokes pot, and throws up in the bathroom of a teen dance club (where you have to be at least 16 to enter). But she does all of it while maintaining her innocence, really. As such, she comes off as a very authentic character. A lot of coming-of-age movies have the central protagonist shedding childhood too quickly. Maeve doesn’t. And that’s why I liked the film. But it was a little slow-moving at times, and there’s a subplot involving Maeve’s friend Ruth, whose estranged father just showed up and wants to meet her. Unfortunately, the Ruth plot really has nothing to do with Maeve’s.

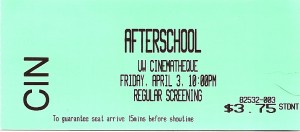

Afterschool is the story of Rob somebody-or-other, who’s a sophomore at a boarding school called Bryton. It’s a co-ed boarding school at that, which is a disaster waiting to happen. (Do such things actually exist? Is anyone really stupid enough to have a co-ed boarding school?) This film is no Catcher in the Rye, that’s for sure. It tries to expose the quiet, unexpressive, YouTube-tinged variety of modern-day teen angst, but its protagonist is pretty unlikeable. He’s pitiable, though, and at one point, he calls home and tells his mom that he doesn’t think anyone likes him; Mom says she doesn’t need the stress of worrying over him and asks him to assure her he’s okay. It’s in this environment that Rob witnesses the school’s popular senior twin girls emerge from a bathroom and fall, bloody and high on drugs/rat poison, onto the floor of an empty hallway. He has been filming the hallway as part of an AV Club project, and so his camera is still running as he walks slowly over to the girls and struggles to help. His back is to us, and it’s clear from the get-go that he’s actually killing one of the girls, but that’s supposed to be a surprise in the final scene of the movie, which “exposes” the reality of the situation.

The film is trying to make some sort of commentary, I’m sure, on how our modern teens seem to be living a series of short video clips rather than life itself. And I suppose the very slow tempo of the movie might further such a message. But it was also really tedious. And the fact that the film’s attempts at mystery and comedy were inappropriate to the mood may have also played into the overall schizoid quality. But they too were really tedious. I found myself looking at my watch repeatedly, and growing increasingly impatient with the unrealistically incompetent teachers. When the movie ended, I couldn’t get out of there fast enough. Maybe that’s what the filmmaker was going for. But watching that movie wasn’t an experience I’d wish on anyone else.

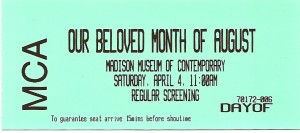

Our Beloved Month of August was sometimes tedious, too. Actually, the first half of this long film (2:30 long) wasn’t just sometimes tedious. The footage is of various aspects of small town life in Portugal, including such things as boar hunts, firetrucks ascending mountain roads, religious processions, karaoke performances, and unemployed men drinking wine. None of it seems to relate to each other, and the only constant is that there are a lot of small-time bands singing at various town festivals. Just when it’s seeming like this is all going nowhere, we get a scene of a producer talking to a director who’s supposed to be making a movie called Our Beloved Month of August. The producer chews him out, saying that none of the work so far has been focused and that the screenplay actually calls for actors. The producer reads the descriptions of the characters, and soon afterward, we get more seemingly unrelated footage — of a high school boy who plays roller hockey and of a young girl who works in a lookout tower, scoping the mountains for fires. But these new additions are more relevant in that the real life characters are suddenly getting together to play in a band and are beginning to enact the plot of the screenplay. The film’s second half mostly delivers the fictional narrative, with occasional jumps (no warnings given) to real life.

The entire movie really coalesces in the final scene, which has the director arguing with the sound guy about how sometimes in the film there are sounds which don’t exist, like music playing when we’re in the woods. The sound guy responds by saying, “So you don’t hear music right now?” just as a song starts playing in the background. The gist of the argument that continues afterwards is that we don’t want to hear all the sounds that exist when we see a film. We don’t want reality unedited. And the movie certainly makes that point. All in all, it does so quite cleverly, but the documentary half of it is a little too long, and though most of the information we get in that first part resurfaces at some point in the second part (a band in the first half becomes a song playing on the radio in the second half, for instance), not all of it connects.

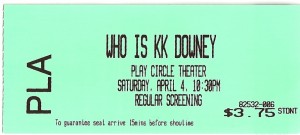

Who Is KK Downey? is a silly film put on by some Canadian sketch comedy group that kind of felt like a film put on by a sketch comedy group. Two failed artists — Theo, whose book Truckstop Hustlers just got rejected, and Terrance, whose girlfriend just dumped him — decide to recast Theo’s book as an autobiography, written by KK Downey, the protagonist of Truckstop Hustlers. Terrance puts on a wig and poses as KK, while Theo becomes his manager. The book becomes a hit, and people gobble up KK’s overly-provocative life as a transgendered prostitute/druggie. There’s a pretty clear parody of James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces, which people loved until they discovered it was fiction. And there’s some commentary on art here (Terrance’s girlfriend is an artist whose claim is “everything deserves a soul,” so she gives eyes to inanimate objects — by gluing googley eyes onto everything). As such, the film feels not-quite-American. Or not quite United-States-of-American, I should say, since comedies here tend not to have a point other than “love conquers all” or some such cliched message. The fact that the movie has an additional layer is a good thing. But the film isn’t hilarious. It’s just funny.

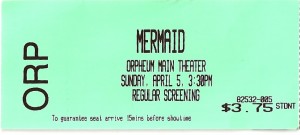

Mermaid was my last movie, and definitely one of the best. Last year, my favorites were The Substitute (a Danish film) and Ben X (a Belgian film). Mermaid is a Russian film, and follows the life of Alisa, a withdrawn but whimsical girl who lives in a seaside shack with her single mother and her grandmother. Alisa’s mother is far more interested in men than she is in Alisa’s welfare, and as a result, Alisa is far more interested in her dreams (many of which include meeting her father) than she is in being a normal girl. The film incorporates some magical realism as Alisa discovers she can make apples fall from trees and cause storms to roll in from the sea. When one such storm destroys the beach shack, the three women move to Moscow, where a teenaged Alisa falls for a rich man who sells plots on the moon. Though she’s often forlorn and forsaken, Alisa is fun and imaginative. So when we watch her take a pathetic job where she walks around the city in a cell phone costume, it’s sad but also full of wonder. One reviewer put it well: “Certainly a level of tenable comparison can – and has to – be made to Amélie; however, make no mistake: here Melikian carves a darker tale of whimsy, rippled by a distinct undercurrent of melancholy not seen in its French counterpart.”